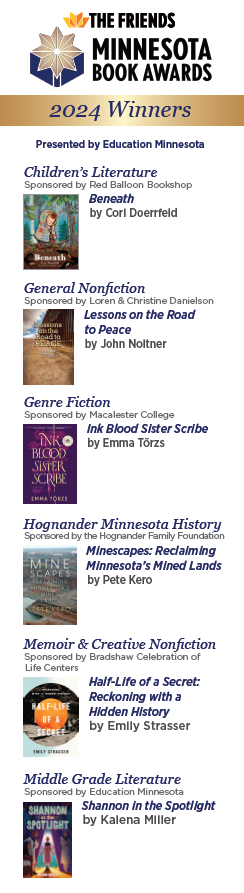

Thanks for your interest in the Minnesota Book Awards!

The Minnesota Book Awards program connects readers and writers across the state with the stories of their neighbors. You can play a vital role in cultivating this statewide program.

We encourage you to promote this year's finalists and winners in your library or bookstore using the assets below. You can offer fresh content for your audience while creating awareness for the Book Awards program at the same time.

Create a finalist book display, post a list of finalist books on social media, or share our exclusive interviews with each finalist from our blog.

Each year, finalists are chosen at the end of January, and winners are announced at the annual Awards Ceremony in April.

2024 Finalist Brochure 8.5x11"

Honored Book Seals

Minnesota Book Awards foil seals are available in silver (finalist) and gold (winner). For additional information, contact [email protected].

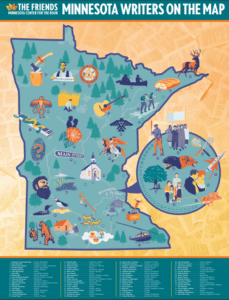

Literary Map

Reading Guides

Download past reading guides for winning books from 2007 through 2016. Great for class discussions and book clubs.

These outreach materials were made possible by support from the Council of Regional Public Library System Administrators (CRPLSA), through the use of Minnesota’s Arts and Cultural Heritage Fund dollars.

"Red: A Crayon's Story" by Michael Hall

2016 Children’s Literature Winner

Published by Greenwillow Books/HarperCollins Publishers

Category sponsored by Books For Africa

Red has a bright red label but he is, in fact, blue. His teacher tries to help him be red by drawing strawberries, his mother tries to help him be red by sending him out on a playdate with a yellow classmate (“go draw a nice orange!”), and the scissors try to help him be red by snipping his label so that he has room to breathe. But Red is miserable. He just can’t be red, no matter how hard he tries. Finally, a brand-new friend offers a brand-new perspective, and Red discovers what readers have known all along. He’s blue!

- Why does everyone expect Red to draw red things? Does it surprise you that no one noticed he was actually blue?

- Red tries hard to draw the strawberries, but practice just doesn’t seem to help. Can everything be practiced? What are some things we can and can’t practice?

- Look at the page that says: “ Everyone seemed to have something to say.” Do you agree with the other crayons’ comments? How might Red feel if he heard that he was “lazy” or wasn’t “applying” himself?

- One crayon replies: “Give him time. He’ll catch on.” Even though the crayon probably meant well, was this a helpful thing to say? Why or why not?

- Until he meets Berry, Red cannot be himself because everyone believes he is different than he actually is. What does Berry do to help Red? Why is this so important?

- Do you have a special friend you feel comfortable just being yourself around? What qualities make that friend so important to you?

- What does Red’s teacher mean when she says Red is really “reaching for the sky”? Can you think of some real-life situations where this expression could be used?

- Why do you think Red’s teacher Scarlet is shorter than Red? Why are his grandparents even shorter than Scarlet?

- Notice that Red is still wearing the masking tape on the final page of the story. Why do you think this is? What does the tape look like?

- If you were asked to draw a self-portrait, but were only allowed to use one color, what color would it be? Why do you think that color represents you best?

Michael Hall is an award-winning author and illustrator whose work has been widely recognized for its simple and engaging approach. He studied biochemistry and psychology at the University of Michigan and worked in biomedical research for several years before becoming a designer. He is the creator of the New York Times–bestselling picture book My Heart Is Like a Zoo (winner of a Minnesota Book Award in 2011) and the acclaimed Perfect Square, Cat Tale, It’s an Orange Aardvark!, and Frankencrayon. He is also the creative director of the Hall Kelley design firm in Minneapolis. Visit www.michaelhallstudio.com.

A conversation with Michael Hall

What inspired you to write Red: A Crayon’s Story?

Forty years ago, a woman named Mickey Myers produced a series of prints based on oversized images of crayons. I was smitten with them. Crayons make an appealing subject. They are joyful and unpretentious, and they can work as a metaphor for many things. I used them several times in my work as a graphic designer. When I began making picture books, I knew that at least one of them would be about crayons. I’ve recently published a second crayon book: Frankencrayon.

What do you hope your readers will take away from it?

I hope Red will be among the many resources that help young children learn about colors. I hope readers of all ages enjoy the antics of Red’s well-meaning friends and family, who simply cannot see beyond his official label. I hope the book will provoke classroom discussions about issues like judging people based on outside appearances, how all of us have both strengths and weaknesses, and the importance of being true to oneself. And I hope Red will inspire reflection about the subtle ways children become mislabeled, about judging children based on their successes rather than their failures, and about the unmitigated joy of finding one’s place in the world.

Did you encounter any interesting challenges in writing and illustrating this story?

There were a lot of questions regarding what the crayon’s world was like. Here are a few:

Can the crayons hover in the air, or are they subject to gravity?

I decided they can float around (possibly supported by an unseen hand) when they are drawing. Otherwise, they’re stuck on the ground.

Where do the crayons live? In a drawer? In a box?

I tried putting the crayons in a number of different places, but the illustrations were too busy. So I decided they simply live in a dark place. The rest is up to the reader to decide.

Do the crayons have faces?

I tend to fall on the side of leaving faces out of places where they don’t occur naturally. Facial expressions can add a lot to a picture book, but I want to leave some of the imagining up to the readers.

How does your background in biochemistry influence your picture books?

I have always been interested in systems. This drew me to the sciences initially and influences my books currently. One of my books, It’s An Orange Aardvark!, while not explicitly about science, can be read as a primer on scientific method. I worry that too few Americans understand the nature of scientific inquiry well enough to develop informed opinions on important issues.

Could you share a little about upcoming books or plans for a future project?

Fall has always been a special time for me. So when my editor asked if I’d be interested in writing a book about autumn, I put a lot of thought into it. I discovered that autumn can be described fairly completely with adjectives that end in ful, like frightful, thankful, colorful, and even wistful. I collected 15 of them, changed each ful to fall, and made 15 rough illustrations. My editor liked it, and the book, Wonderfall, is coming out in September, 2016.

“No House To Call My Home: Love, Family, and Other Transgressions” by Ryan Berg

2016 General Nonfiction Winner

Published by Nation Books/Perseus Books Group

Category sponsored by The Waterbury Group at Morgan Stanley

In this lyrical debut, Ryan Berg immerses readers in the gritty, dangerous, and shockingly underreported world of homeless LGBTQ teens in New York. As a caseworker in a group home for disowned LGBTQ teenagers, Berg witnessed the struggles, fears, and ambitions of these disconnected youth as they resisted the pull of the street, tottering between destruction and survival. Focusing on the lives and loves of eight unforgettable youth, No House to Call My Home traces their efforts to break away from dangerous sex work and cycles of drug and alcohol abuse, and, in the process, to heal from years of trauma.

- Berg suggests that the narrow focus on marriage equality among LGBTQ rights advocates has resulted in the neglect of other pressing issues. What does he see as the intersecting challenges that LGBTQ individuals face?

- In the introduction, Berg states: “This isn’t a story of a white man attempting to “save” or speak for young queer people of color. I do not claim their experiences as my own.” How does he acknowledge the skewed power dynamic between himself and the youth he writes about in the narrative?

- We meet Benny after years in foster care. At the end of the chapter 1 he is about to graduate from high school and he’s optimistic, saying: “Things are going to be good. I can feel it.” What are the challenges that Benny will face outside the system? How is he prepared or ill-prepared to live independently and why?

- By conventional standards, Alexander is more successful than his peers. What qualities or actions were instrumental in achieving that success? How does his past differ from the other youth in the book?

- Berg points out that there is an overrepresentation of youth of color in the foster care system and that some benefit from the system while others are oppressed by it. What is the correlation? What is Berg suggesting?

- When noting ways to combat LGBTQ youth homelessness, Berg says: “More beds in shelters are a temporary solution, a Band-Aid for a gushing wound.” He is suggesting that in order to eradicate youth homelessness we need to address the causes of homelessness: racial disparity, homophobia/transphobia, subpar mental health services, and systemic oppression. Do you agree or disagree? Why?

- Berg interacted with the youth in the book for two years and witnessed most of the events that he describes. How might the book be different if Berg had chosen to remove himself from the narrative? Why did he choose to include himself as a character?

- How have your ideas of power and privilege changed since reading No House to Call My Home? Were there moments when you felt empathy for the youth in the book? Were there moments when you felt alienated? If so, when and why?

Ryan Berg is a Lambda Literary Foundation Emerging Writers Fellow and holds an MFA in Creative Writing from Hunter College in New York. He received the New York Foundation of the Arts Fellowship in Nonfiction Literature in 2011 and has been awarded artist residencies from the MacDowell Colony, Yaddo, and Virginia Center for the Creative Arts. His work has appeared in Ploughshares, Slate, The Advocate, Salon, Local Knowledge, and The Sun. In addition to writing, Berg is the Program Manager for ConneQT Host Home Program in Minneapolis, where community members share their homes and resources with LGBTQ youth experiencing homelessness. Berg has spoken at universities and conferences across the country discussing youth homelessness and the host home model. Visit www.nohousetocallmyhome.com.

Could you describe how you came to work as a residential counselor for LGBTQ youth in New York City?

I started working with LGBTQ youth in foster care in 2004. I’d been working in theater before that and was feeling the conversations within that community were taking place in silos. I felt a need to do something outside myself, so I applied to work at a group home.

Did you experience the events depicted in the book with a mind toward writing about them one day? At what point did you decide this story needed to be told?

I hadn’t intended to write about the youth, it felt too exploitive. I didn’t want my writing to steer my experiences with them. During the summer of 2005 I went to the University of Iowa for a creative writing workshop for social workers and it was there I put down the first pages. I was encouraged by the instructor to continue writing after the workshop ended. Once I returned to New York I shelved the pages, and focused on working with the youth again. It wasn’t until I left my position and started an MFA at Hunter College that I realized I couldn’t shake these stories. I really felt an urgency in telling them. These stories felt unavoidable. There was nothing being said about the youth experience of homelessness in the media, especially LGBTQ youth. We know the statistics – 40% of homeless youth identify as LGBTQ – but statistics become numbing. People really operate from empathy. My goal was to open a door into an unseen world, to focus on the lives of the young people experiencing the hardships that were addressed in the book.

The book was published ten years after your time at the 401 and the Keap Street Youth Home. How did your writing change over the course of those ten years?

I learned about humility writing this book, I learned about privilege. The writer who wrote the initial pages in 2005 was a much more sentimental, naive person. Over the course of writing the book I became more aware of issues of mass incarceration, systemic oppression, racial and economic justice, and the role of well-intentioned white social workers in the lives of young people of color. I learned about power, about the uncomfortable reality of my own power. I had to turn the lens inward and do some work on myself in order to attempt to do these stories justice. There’s a great responsibility in writing about others. The inherent challenge was how to do it while honoring their stories and their privacy. Writing about others – especially people already marginalized – creates such a skewed power dynamic. I wanted to make sure that I was exercising that power as justly as I could. I needed to interrogate my motives for writing the story. I was aware of my own privilege and power in that moment and tried not to shy away from it. My hope is that this book creates space for LGBTQ youth experiencing homelessness to tell their own stories, that their own memoirs begin to emerge, becoming the necessary corrective to history.

What do you hope your readers will take away from No House to Call My Home? Have there been any surprising outcomes since its publication?

Many people think “homeless” and picture a stereotype. We need to deepen the conversation. I hope readers see the nuance and complexity and resilience of the young people in this book and are moved to evoke change within their own communities. The circumstances of these young people’s lives are disturbing, but all they experienced and expressed – the love, the loss, the turmoil, the betrayals – all these are universally human things and things anyone can relate to. The surprising and rewarding moments are when young people contact me and thank me for writing the book. Recently, a high school student came up to me after a reading. She told me her parents refused to accept her identity. She came home one day to find that they had moved away without telling her, leaving her homeless. She said she saw herself reflected in the story I read. Not only in the family rejection, but in the resiliency. She talked about how she doesn’t make it to school as often as she’d like because right now work is more important. She needs to survive. She said, “I just wanted to thank you. I feel so invisible in my life. Listening to you felt like being seen.” If this book touches one young person and helps them rediscover their value, I feel the book has done its job.

Share a little about your current work in Minneapolis and any plans you may have for a future writing project.

I’m the program manager for the ConneQT Host Home Program. ConneQT Host Home, a program of Avenues for Homeless Youth, is a community and volunteer-based response to youth homelessness. All youth who participate in our program are queer-identified and matched with hosts. Hosts in the program are adults who open their homes and their hearts to young people who are looking for a healthy and stable connection, in addition to basic needs. The length of stay is anywhere from 1 week to 3 months.

My next writing project is about bullying, trauma, and LGBTQ youth suicide. Communities are failing our young people and I believe the subject needs thoughtful attention.

Jennifer Harveland reviews No House to Call My Home: Love, Family, and Other Transgressions

"The Grave Soul” by Ellen Hart

2016 Genre Fiction Winner

Published by Minotaur Books

Category sponsored by Macalester College

When Guthrie Hewitt calls on restaurateur and private investigator Jane Lawless, he doesn’t know where else to turn. Guthrie is ready to propose to his girlfriend Kira, but his trip to her home over Thanksgiving made him uneasy. All her life, Kira has been haunted by a dream in which she witnesses her mother being murdered, but she knows it can’t be true because the dream doesn’t line up with the facts of her mother’s death. After visiting Kira’s home for the first time and receiving a disturbing anonymous package in the mail, Guthrie starts to wonder if Kira’s dream might hold more truth than she knows. Ellen Hart once again brings her intimate voice to the story of a family and the secrets that can build and destroy lives.

- In The Grave Soul, Hart poses the often complex question of what moral obligations family members have to one another. Did you agree with the decisions the Adlers made to protect one another? Could you see yourself making similar decisions to protect a loved one?

- What did you think about the nonlinear structure of the story? How would the novel’s impact have been different if the events had been revealed in chronological order?

- Why does Laurie feel a moment of panic when she first sees the face of the injured woman on New Year’s Eve? Do you think she and Hannah dealt with the situation as well as they could have that night?

- As Jane and Guthrie discuss the case, Jane asks: “You really want to pay me to prove that someone Kira loves is a murderer?” Do you think Guthrie was right to meddle with the Adler family’s secrets? Would Kira have been better off never knowing the truth?

- Why did one family member take photographs of the crime scene and conceal them for so many years? Did you correctly guess the identity of the person responsible for mailing the photos to Guthrie?

- What controversial changes does Hannah want to make at the farmhouse? Do you think her proposed solution is a realistic one?

- Why does Laurie blame herself for Kevin’s unhappiness? What was the “epic failure of imagination” that sealed her fate?

- Jane learns about Delia Adler by questioning several people in New Dresden – Hannah Adler, Riley Garrow, Katie Olsen, Father Mike, and others. What do we find out about Delia through these combined accounts? What sort of mother and wife was she?

- Once you understood the killer’s motive for murdering Delia, did you find yourself feeling any sympathy toward him/her? Was the killer’s moral suffering punishment enough for the crime?

- What do you make of Jane’s decision to simply pass the evidence along to Guthrie instead of taking action against the killer herself? What do you believe Guthrie will do with the information Jane has uncovered?

Ellen Hart is the author of more than thirty crime novels in two different series. She has won innumerable awards for her writing, including being a six-time winner of the Lambda Literary Award for Best Lesbian Mystery, a four-time winner of the Minnesota Book Award, a three-time winner of the Golden Crown Literary Award in several categories, a recipient of the Alice B. Medal, and status as an official GLBT Literary Saint at the Saints & Sinners Literary Festival in New Orleans in 2005. In 2010, Ellen received the GCLS Trailblazer Award for lifetime achievement in the field of lesbian literature. Visit www.ellenhart.com.

You’ve said before that the titles of your novels tend to come first. How did the title of this book come to you and how did it inform the story?

Titles always come first for me. They help me thematically, assist me in finding my way into the story. I don’t remember what I was reading, but I came across a Dorothy Dix quote, “The grave soul seeks its own secrets, and takes its own punishment in silence.” I knew I wanted to write about a secretive, tightly-knit family in my next book. The family lived in a small town in rural Wisconsin. I began to see how the title resonated – they all guarded dark family secrets. In the end, keeping secrets exacts its own kind of punishment. I followed that theme through the book.

The nonlinear structure of The Grave Soul makes for a spectacular beginning. What made you decide to format the book in this way?

The opening chapter was the first image that came to me. It seemed like such a striking situation that I knew I had to use it. The non-linear approach was the only way I could get away with it. We start toward the end of the story, double back to the beginning, move through the story, and them come back to the end. I worked hard to make sure that structure was understandable. I’d never used a structure like that before, so it produced some interesting challenges.

After twenty-three books, how have the characters of Jane and Cordelia evolved? How have they surprised you?

Both characters have surprised me. My main character, Jane, has always been a hard nut for me to crack. I’ve never entirely understood her. That may sound strange, or even a little precious, but it’s true. I enter my stories – and my characters – very much the way the reader does. I come to them over time, understand them as I see them act and react. For instance, the character of Cordelia always loathed children. I make a big point of that…until she takes over the parenting of her niece. In a sense, it’s the first time she truly falls in love.

When did you decide you wanted to become a writer? What drew you to writing mystery novels, in particular?

I believe that many people who love to read also secretly want to write. In my middle thirties I decided that if I didn’t give writing a try, I’d come to the end of my life with a huge regret. I’d always loved mysteries and when a mystery idea came calling, I decided to act on it. That was twenty-eight years ago. I’m currently at work on my thirty-third mystery.

What challenges you most in your writing?

Keeping it fresh. Raising the bar with each book. Challenging myself to go deeper into the characters, to understand more fully what makes us do what we do – what makes us human.

"Water and What We Know”

by Karen Babine

2016 Memoir & Creative Nonfiction Winner

Published by The University of Minnesota Press

Category sponsored by Kevin and Greta Warren

Download a print-friendly version

In essays that travel from the wildness of Lake Superior to the order of an Ohio apple orchard, Babine traces an ethic of place and explores the link between landscape and identity. From the headwaters of the Mississippi River in Itasca State Park, she considers the desire that drives the idea of the North. The bite of a Honeycrisp apple grown in Ohio returns her to her origin in Minnesota and to pie-making lessons in her Gram’s kitchen. In the Deadwood, South Dakota, of her great-great-grandfather, she pursues what the Irish call dinnseanchas, or place-lore. And through it all Babine searches out the stories that water has written on human consciousness, revealing again and again what their poignancy tells us about our place and what it means to be here.

- Stories of Babine’s family are woven throughout the pages of this collection. Were there any particular stories that stood out for you? How do you think her family and background served her well in becoming a writer?

- What does Babine mean when she says, “An ethic of place requires a certain level of discomfort”?

- How did you respond to Babine’s account of the 1997 Red River Flood? Why do disaster narratives form such a foundational part of a community? How does she think one’s relationship to a recently flooded place is different than to a place that has seen a wildfire or a tornado?

- Part of Babine’s fascination with the 1980 Mount St. Helens eruption comes down to the fact that “something happened to change the physical and mental landscape” and she was alive when it happened. What does she mean by “mental landscape”? Have you experienced events in your lifetime that have changed the physical and mental landscape of a community?

- Language and etymology appear frequently throughout the collection as Babine examines word origins and how words connect us to the places they represent. Why is it important to understand the connection between language and place?

- How much do you know of your own ancestry? Did reading “Deadwood” make you wonder about your own background and how it might have shaped who you are today?

- In “Grain Elevator Skyline” Babine writes: “The existence of the homeplace separates the Heartland from other parts of the country.” What is “homeplace” and why does she consider it to be an important aspect of the Heartland mythology?

- Several ethical and environmental questions are raised in the essay “Faults.” How do we control natural disasters – and to what extent should we? Is it a natural disaster if people are not affected, property not destroyed? Are we coming closer to the point where politics and economics finally decide that fossil fuels are not worth the earthquakes and pollution that result from their extraction? How would you respond to these questions?

- Babine clearly did a great deal of research in writing these essays. What have you learned from reading the collection and which topics are you interested in exploring further?

- Is there a particular place where you feel physically and emotionally at home? What does it mean to inhabit that place?

Karen Babine is the founder and editor-in-chief of Assay: A Journal of Nonfiction Studies. She was born and raised in the Lakes Country of Hubbard County, Minnesota. She traded lakes and trees for prairie and grass on the Red River Valley of western Minnesota for college, then went west to Spokane to earn her MFA in creative writing from Eastern Washington University. Her PhD in English is from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. Her interests include place studies and travel writing, contemporary Irish literature, literary heritage, teaching creative writing and all forms of nonfiction. Her essay “An Island Triptych” was listed as a Notable in the 2014 Best American Essays. She lives and writes in Minneapolis. Visit www.karenbabine.com.

What inspired you to write this essay collection? Did you set out with a focus on place and identity, or did the common thread materialize later in the process?

Like many first collections, this one wasn’t designed in one piece. In fact, the earliest pieces in this book I wrote when I was a senior in high school. I wrote the majority of it during my Masters of Fine Arts program, two years that did so much to shape how I envisioned myself in the conversation of environmental writers. In the years since, some essays were removed, some added. Once I had something about the right length, and an order that seemed logical, I looked for the thread between all these very different essays on very different landscapes and landscape events, and the idea of water became obvious. I knew early in the process that I was interested in exploring this idea of place, but I didn’t fully articulate what I consider an ethic of place until I wrote the introduction (the last thing I wrote).

Could you describe the research you undertook in writing these essays?

The best part about being an essayist is the research. It’s my idea of fun. Most of the essays start with something I read, something discussed on a podcast, current events, anything. For instance, “Recorded History,” about volcanoes, began when I learned that the 1980 Mt. St. Helens eruption was the largest landslide in recorded history. Really? In all of recorded history, that was the largest? So I started researching volcanoes for other “largest” moments, which led me to things like learning that Frankenstein was written because of the 1815 Mt. Tambora eruption. Research’s purpose is to lead me to those moments of intersection, of ohhhhhhh, I never thought about it that way before.

What do you hope your readers will take away from Water and What We Know?

I want readers to be able to find their universal in my specific, to consider how the places they are connected to shape how they think about the world. Often, we don’t consider local knowledge a valid form of knowledge, but when we think about what we know, because we are here right now, we know quite a bit.

How and when did you first decide you wanted to be a writer? Please share a little bit about your journey in becoming a published author.

I’m one of those who’s been writing since I could hold a crayon, so through high school, college, my MFA, my PhD, it’s been about honing my craft, discovering new writers who are writing similar work, becoming a greater part of the literary community. I was able to publish young, through the High School Writer, a newspaper-magazine that published high school writing (out of Grand Rapids), to learning in college that literary journals existed. To find the right press for this book, it was a matter of looking at my shelves of my favorite environmental nonfiction and seeing who published them. I’m so grateful my book landed at the University of Minnesota Press: a Minnesota book on a Minnesota press is quite a gift.

Have you always been drawn to creative nonfiction or did you start out writing in other genres?

I have dabbled in other genres, but I find nonfiction fits my brain waves best, the ideas and questions and simple joys that can exist in an essay. I always find myself coming back. A writer can learn a thousand things from writing in other genres and at the moment, I find myself in a micro-essay project, which is outside my comfort zone, but it’s been fun to play with.

How does being a Minnesotan and the community in which you live inform your writing?

When I was a sophomore in college, I took a Minnesota Writers class. It remains the most important literary moment in my life. (Thanks, Joan Kopperud!) But in that class, we read Paul Gruchow’s Boundary Waters—and I had no idea that he was teaching in our English department at the time. It was the first time I realized that I could write about Minnesota, I could write about rural Minnesota, people would care, it could be published, and, as Gruchow had just won the Minnesota Book Award for Boundary Waters, it could win awards. Minnesota is the most vibrant literary community in the country and there is no better place to be a writer.

Could you share a little about your current work or plans for a future project?

I’m working on a micro-essay collection about my mother’s recent cancer diagnosis/treatment, becoming obsessed with cast iron and cooking with it, and being incredibly disturbed by the food metaphors of cancer. Her doctors talk about chemo infusions, of seeds, of her cabbage-sized tumor. And so these very short essays (250, 750, or 1500 words) examine very specific minute aspects of those, from roasting chickens and making chicken stock (as a vegetarian) to making eggs with my favorite cast iron skillet. It’s unlike anything I’ve ever done before (and when it’s done, I’m back to place writing), but you go where the writing wants you to go. I wouldn’t have chosen to write this on my own, but it’s good for me to stretch who I am as a writer.

Read a great three-part interview with Karen Babine on Jactionary: A Book Lover’s Blog

Part One: Ghost Runners, Minnesota Writers, & Irish Crime Fiction

Part Two: The Triangular Prism, Water and What We Know, & Galway

Part Three: Butt in Chair, Wanderlust, & Author Desert Island

“Minnesota Modern Architecture and Life at Midcentury” by Larry Millett

2016 Minnesota Winner

Photos by Denes Saari and Maria Forrai Saari

Published by University of Minnesota Press

Category sponsored by Saint Mary’s University of Minnesota

Larry Millett lends his expert eye to this guide through the life and architectural styles of Minnesota at midcentury. Richly illustrated, this book is an exploration of the post- World War II architectural style that swept the nation from 1945 through the mid-1960s. Millet takes us through twelve midcentury Minnesotan homes, and unpacks the evolution of sites as varied in nature as the St. Columbia Catholic Church in St. Paul and the expansive IBM complex in Rochester. Minnesota Modern provides a close-up view of a style that penetrated the social, political, and cultural machinery of the times – one that made lasting changes to the landscape of Minnesota architecture.

- Proponents of Midcentury Modernism believed this new form of architecture, “liberated from the burdens of tradition, would lead the way to a better world.” In what ways were they right?

- How was Midcentury Modernism more than just a style? What are the core ideas of this philosophy?

- World War II had a profound impact on this style of architecture. What were the factors that contributed to its influence?

- What were some drawbacks to the explosion of modern architecture?

- Millett states that Midcentury Modernism emerged at a time when Minnesota, and especially the Twin Cities area, “was on the verge of vast and lasting changes in how people lived.” What were some of those changes and do you still see them reflected in Minnesota today?

- Why did so many of the ‘experimental city’ projects, like that of Spilhaus, fail to come to full fruition?

- What were some of the benefits and negative consequences of the drive for urban renewal in Minneapolis and St. Paul?

- What aspects of Midcentury Modernism architecture attract you? Which do you find less appealing?

- Southdale Mall is called one of 10 buildings that changed America. Do you think it was changed for the better or for the worse?

- How were the ideals of this period reflected in the houses of worship built during this time, for example, Christ Lutheran in Minneapolis or Saint John’s Abbey in Collegeville?

- How did the format of Minnesota Modern affect your reading, with the Midcentury Modern Houses sections interspersed with the other chapters? Did it help you get more of a feeling for the period? Why or why not?

Larry Millett, a native of Minneapolis, is a graduate of St. John’s University, Collegeville, Minnesota (BA, English, 1969) and the University of Chicago (MA, English, 1970). He spent much of his career as a writer, reporter, and editor for thePioneer Press, joining the newspaper in 1972. In 1984, he won a Knight Fellowship to the University of Michigan to study architectural history and theory. When he returned to St. Paul in 1985, Millett became the newspaper’s first architecture critic. He held that post until his retirement from the Pioneer Press in June of 2002. Millett has written articles for many publications, including Architecture, Inland Architect, Architecture Minnesota and Minnesota History magazines. He has written eleven works of non-fiction, including Minnesota’s Own: Preserving Our Grand Homes, Once There Were Castles and the AIA Guide to the Twin Cities, as well as seven mystery novels. Visit www.larrymillett.com.

What inspired you to focus on Midcentury Modernism for this most recent book?

I grew up in the 1950s, and the modern architecture of that era became a big part of my life, so I’ve always been interested in it. I also thought it was a subject that, in Minnesota at least, hadn’t received much scholarly attention. With that in mind, I decided that a big survey of midcentury architecture in the context of the times, which saw the Twin Cities transformed by suburban growth and urban renewal, would make for an intriguing book.

Describe the research you undertook in writing it and any challenges you may have encountered along the way.

My biggest challenge centered on the fact that very little secondary literature deals with midcentury modernism in Minnesota. As a result, I had to do mostly primary research. A big part of my job was developing a list of significant midcentury buildings in Minnesota. I also conducted many interviews as part of my research, which took more than three years.

How did you initially become interested in writing about architecture? Please tell a little about your path to becoming a journalist and later a published author.

I started drawing building plans when I was ten years old, and I thought for a time that I would become an architect. That didn’t happen. Instead, I ended up in college as an English major and then fell into a long career in journalism. Even so, I never lost my deep interest in architecture. In my late thirties, I received a fellowship to study architectural history and theory at the University of Michigan, after which I became the architecture critic for the St. Paul Pioneer Press. That experience led me into writing books about architecture and urban history. My first book to reach a wide audience was Lost Twin Cities, published by the Minnesota Historical Society Press in 1992.

When and how did your interest in writing mystery novels develop? Is it difficult to balance this type of writing with your nonfiction work?

I’ve been reading mystery fiction my whole life, beginning with the Sherlock Holmes stories when I was a kid. I always had an idea in the back of my mind that maybe I could write mystery fiction someday. With my interest in history, I thought I’d be best suited to writing historical mystery fiction, and that’s how I ended up bringing Holmes to Minnesota in my first novel, Sherlock Holmes and the Red Demon, published by Viking Penguin in 1996. Balancing fiction and nonfiction isn’t difficult for me because I love writing both types of books. However, I never try to write both at the same time. It’s either one or the other.

How does being a Minnesotan and the particular community in which you live inform your writing? Do you imagine you would have had a similar career had you grown up in a state other than Minnesota?

I’m a Minnesota guy through and through, even though I don’t fish or play hockey. I grew up on the North Side of Minneapolis but, being an adventurous soul, moved to St. Paul more than 40 year ago. St. Paul is steeped in a tradition of great writers, and I can’t imagine doing what I do anywhere else. When I was in my twenties, I nearly took a newspaper job in Portland, Oregon. I’ve often wondered how such a move would have affected my career, but there’s really no way of knowing. As it is, I have no regrets about staying close to home.

Could you share a little about your current work or plans for a future project?

I’ve just completed a new mystery novel called Sherlock Holmes and the Eisendorf Enigma, set near Rochester in 1920. It will be out in spring 2017. The novel depicts an old and somewhat fragile Holmes facing off against a monstrous killer from his past. I’m not sure what will come after that – maybe a book about downtown urban renewal in Minneapolis and St. Paul after World War II, or maybe a new Shadwell Rafferty adventure

“There's Something I Want You To Do"

by Charles Baxter

2016 Novel & Short Story Winner

Published by Pantheon Books/Random House

Category sponsored by Education Minnesota

From one of the great masters of the contemporary short story, this outstanding collection showcases Charles Baxter’s unique ability to unveil the remarkable in the seemingly inconsequential moments of everyday life. Penetrating and prophetic, the ten interrelated stories are held together by an intricate web of cause and effect—one that slowly ensnares both fictional bystanders and enraptured readers. Benny, an architect and hopeless romantic, is mugged on his nightly walk along the Mississippi River. A drug dealer named Black Bird reads Othello while waiting for customers in a bar. Elijah, a pediatrician and the father of two, is visited by visions of Alfred Hitchcock. As the collection progresses, we delve more deeply into the private lives of these characters, exploring their fears, fantasies, and obsessions. The result is a portrait of human nature as seen from the tightrope that spans the distance between dreams and waking life.

- The characters in this collection slip in and out of each other’s stories, eventually becoming part of a larger pattern of interconnections. What is Baxter trying to demonstrate with this multiplicity of perspectives? What were some of your favorite discovered connections?

- Most of the stories touch down at some point in Minneapolis and several of them—specifically “Chastity,” “Charity,” and “Sloth”—find the characters gravitating toward the Mississippi River. What role does the setting play? What sort of language does Baxter use to describe the river?

- Baxter makes use of dreams and visitations throughout the stories, most notably for the characters of Amelia and Elijah. Why is the space between the waking world and the spirit world so permeable within the landscape of this collection? Do you believe Elijah’s experience is wholly imagined, or could a visitation such as his be possible?

- One reviewer called Baxter “a master at describing uncomfortable situations hovering between comedy and pain.” Which scenes fit this description and what about the language or style makes them so effective?

- Consider the titles of the stories. The moral implications are clear, but the themes are seldom expressed directly. Discuss how each title appears thematically in its story and what it means in the context of the narrative.

- Dr. Elijah Jones is the central figure in three of the stories and makes brief appearances in several others. How did your opinion of him change throughout the collection? Do you believe the story he told Susan about being a hero at the end of “Bravery”? What do think will happen to him after the critical conclusion of “Gluttony”?

- Another character, Benny, is the central figure in more than one story. How would you describe him? Do you think he would have fallen in love with Sarah had he met her under different circumstances?

- Why do you think Baxter chose to re-introduce Dolores in the second half of the collection? How does reading “Avarice” change your understanding of the Dolores we initially met through Wesley’s eyes in “Loyalty”?

- Baxter has said that the idea for centering these stories around “request moments” initially came to him while attending a production of Hamlet. He realized that many of Shakespeare’s plays begin with an important request that sets the story in motion. How do the fictional situations created by request moments mirror what we experience in our daily lives? How much of what we do every day is bound by social obligation? Are there specific examples of request moments in your own life that have forced you down an unexpected path?

Charles Baxter is the author of five novels, including The Feast of Love (nominated for the National Book Award in 2000); five collections of short stories; three collections of poems; and two collections of essays on fiction, including The Art of Subtext: Beyond Plot (winner of the 2008 Minnesota Book Award in General Nonfiction). His stories “Bravery” and “Charity,” which appear in There’s Something I Want You to Do, were included in Best American Short Stories in 2013 and 2014, respectively. Baxter was born in Minneapolis and graduated from Macalester College in Saint Paul. After completing graduate work in English at the State University of New York at Buffalo, he taught for several years at Wayne State University in Detroit and later moved to the Department of English at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. He now lives in Minneapolis and teaches at the University of Minnesota. Visit

You explore a wide range of request moments in this collection. What inspired you to structure the stories around requests? Where does the phrase “there’s something I want you to do” come from?

I had noticed that many of Shakespeare’s plays, including Hamlet, begin with request moments that sets the plot into motion. Such requests put someone in a really interesting position, especially if the person who issues the request says something like, “If you love me, you’ll do this for me.” Requests can define relationships, I think. A request is often at the heart of a social obligation, especially if the clock is ticking and time may run out. As for the phrase itself, it was something that my mother often said to me whenever I came home from school and walked through the front door.

How did you come to conceive of this book as a collection of linked stories with recurring characters?

The first two stories more or less wrote themselves, and I noticed that they both had titles with the names of virtues—bravery and loyalty—and I thought: “That’s very interesting. I guess I’m writing a book about the virtues.” But I didn’t want to write a book about virtues because who would read it? Virtues can be a little dull. And safe. So I thought I’d write a kind of decalogue, a book with five virtues and five vices, and someone suggested to me that the characters who show up in the virtues should also show up in the vices, and I thought that was a great idea, so I did it.

What is the role of dreams and visitations in the otherwise realistic landscape of the book?

I think dreams are part of our daily (or nightly) lives, so dreams aren’t really distinct from realism or inimical to it. Our dreams haunt us, which makes them a good source for stories. As for the visitation, especially the one in “Sloth,” I simply believed it was possible and that people do sometimes experience such things, especially when they’re under great stress, as Dr. Jones is in that story.

What do you hope readers will take away from this collection? Have there been any surprising reactions to the work?

I hope readers will enjoy the stories and take pleasure from reading them. That’s first and foremost. So far I haven’t had any surprising reactions, except that a couple of people have told me that they were haunted by the stories (which is good).

Could you share a bit about your path to becoming a published author?

It helps to have been struck by lightning early. A few works of literature hit me right between the eyes in high school, and I thought, “I really want to write a book that will do that to other people.” I had many discouragements, many nasty letters from editors, when I was starting out, but I was stubborn and obstinate and began to get my stuff published by the time I was in my late thirties. I must have been a slow learner.

What challenges you most in your writing?

I think the greatest challenge is to find a story that’s both entertaining and meaningful. I like to have material that gives off a comic quality, if I can, but that doesn’t always work. Both comedy and suspense (urgency and momentum) are terribly hard to build into a story. The greatest challenge of all is not to bore the reader—to keep things moving, lively, truthful.

What are you working on now?

A novel. It was called The Mall of America and then it was called The Sun Collective, and by the time I finish it, I don’t know what it’ll be called.

SELCO communications specialist Jennifer Harveland reviews There’s Something I Want You to Do by Charles Baxter:

Charles Baxter reads from and discusses his short story collection, There’s Something I Want You to Do, at the Center for Fiction:

PRX’s First Draft highlights the voices of writers as they discuss their work, their craft and the literary arts. This episode features an interview with Charles Baxter, author of the short story collection There’s Something I Want You To Do. Listen >>

“Beautiful Wall” by Ray Gonzalez

2016 Poetry Winner

Published by BOA Editions, Ltd.

Category sponsored by Wellington Management

With the poems of Beautiful Wall, Ray Gonzalez takes readers on a profound journey through the deserts of the Southwest where the ever-changing natural landscape and an aggressive border culture rewrite intolerance and ethnocentric thought into human history. Inextricably linked to his Mexican ancestry and American upbringing, Gonzalez mounts the wall between the current realities of violence and politics, and a beautiful, never-to-be-forgotten past.

- The Southwest desert becomes a character in Gonzalez’s collection. What are some of the ways in which he makes the desert landscape come alive?

- Gonzalez himself has talked about the importance of place in his work. Where do you see that most strongly in Beautiful Wall?

- While Gonzalez has specific poems about Aztec gods, other gods are present in many of the poems, taking the form of animals or poets. In which poems do you see other figures taking on ‘god-like’ powers?

- Walls and borders come up in many fashions throughout the collection. How does the way Gonzalez uses the concept of a border in these poems make you understand the depth of the history in places like El Paso and La Mesilla?

- How do you feel the two poems focused on the poet’s battle with depression (“Drums,” “Hospital”) fit within the larger context of the collection? What are some of the same images or themes that appear in these poems?

- There is powerful landscape imagery throughout the collection–which poems stood out for you and why?

- One reviewer called Weldon Kees “Virgil to Gonzalez’s Dante” in the poem “Crossing New Mexico with Weldon Kees.” How does Gonzalez pay tribute to Kees in the poem, and what do you think he learns from the other poet during the course of the poem?

- There are several poems in which birds are featured. How do you view Gonzalez’s frequent connection with them and the role they play in his poetry?

- Threads of violence and war run through many of the poems: WWII, the atomic bomb, the Iraq war, and past and present violence in Juarez. Does reading these poems shed new light on historical or present circumstances for you?

- Music is another strong influence for Gonzalez throughout his body of work, and in Beautiful Wall he reimagines the experiences of musicians like Bob Dylan, Don Van Vliet, and Duane Allman. Who are the musicians that evoke strong feelings of nostalgia and connection for you?

- What were your first impressions when you encountered the title of this collection? What did you think it meant? Has your sense of the title changed after reading the book?

Ray Gonzalez is the author of fifteen books of poetry, including previous Minnesota Book Award winners, Turtle Pictures (University of Arizona Press, 2000) and The Hawk Temple at Tierra Grande (BOA Editions, Ltd., 2002). His poetry has appeared in multiple editions of The Best American Poetry and The Pushcart Prize: Best of the Small Presses 2000. Gonzalez is also the author of three collections of essays and two collections of short stories, and the editor of twelve anthologies, most recently Sudden Fiction Latino: Short Short Stories from the U.S. and Latin America. He has served as Poetry Editor for The Bloomsbury Review for thirty-five years and, in 1998, founded the poetry journal LUNA, which received a Fund for Poetry grant for Excellence in Publishing. He was awarded a 2002 Lifetime Achievement Award from the Southwest Border Regional Library Association, and is currently a professor in the MFA Creative Writing Program at The University of Minnesota in Minneapolis.

You have an extensive publishing career. How does Beautiful Wall compare to your prior poetry collections?

Beautiful Wall contains poems about the Southwest but also some Minnesota poems, as well as poems about my nephew who died in the Iraq war.

A number of these poems focus on other writers and musicians. What drew you to these figures?

When I write about famous figures, I am acknowledging their influence and imagine parts of their lives.

What do you hope readers will take away from this collection?

Perhaps readers can see that the best and most honest poetry comes from everyday life.

After so many years living in Minnesota, why does the landscape of the Southwest remain so important to your poetic drive?

Image is everything in poems and the desert landscape I grew up in never leaves me and propels my creativity to form words on the page.

How and when did you realize you wanted to become a writer?

Three things made me a writer. The influence of my grandmother telling me stories when I was a child, The Beatles appearing on TV in 1964 changed my life when I saw and heard it was okay to rhyme words, and having a great poetry teacher in college. My late mentor Robert Burlingame opened my eyes to poetry.

How has teaching influenced your own writing?

Teaching brings me closer to other writers as we share common experiences and ideas. I get to share what I know and this generates new work for me.

Music plays a part in much of your work. What are your thoughts on the relationship between music and poetry? Do you listen to music while you write?

As I said earlier, rock music was and remains a major influence. All poetry has music. I always write to music.

Awake in the desert to the sound of calling.

Must be the mountain, I thought.

The violent border, I assumed, though the boundary

line between the living and the dead was erased years ago.

Awake in the sand, I feared, old shoes decorated with

razor wire, a heaven of light on the peaks.

Must be time to get up, I assumed. Parked outside,

Border Patrol vehicles, I had to choose.

Awake to follow immigration shadows vanishing inside

American walls, river drownings counted as they cross,

Maria Salinas’ body dragged out, her mud costume

pasted with plastic bottles and crushed beer cans,

black water flowing to bless her in her sleep.

Must be the roar of illegal death, I decided,

a way out of the current, though satellite maps never

show the brown veins of the concrete channel.

Awake in the arroyo of a mushroom cloud, I choke,

1945 explosion in the sand, eternal radioactive wind,

the end of one war mutating the border into another

that also requires fatal skills of young men because few

dream the atomic bomb gave birth in the Jornado,

historic trail behind the mountain realigned, then cut

off from El Paso, the town surrounded with barbed

wire, the new century kissing car bombs, drug cartels,

massacres across the river, hundreds shot in ambushes

and neighborhood soccer games that always score.

Wake up, I thought, look south to the last cathedral

in Juarez before its exploding bricks hurtle this way.

Make the sign of the cross, open your eyes to one town,

two cities, five centuries of praying in the beautiful dust.

Poem courtesy of BOA Editions, Ltd.

Superstition Review: Four Poems by Ray Gonzalez

“Degrees of Freedom: The Origins of Civil Rights in Minnesota, 1865-1912” by William D. Green

2016 Hognander Minnesota History Award Winner

Published by University of Minnesota Press

Category sponsored by Hognander Family Foundation

Spanning the half-century after the Civil War, Degrees of Freedom: The Origins of Civil Rights in Minnesota, 1865-1912 draws a rare picture of black experience in a northern state and of the nature of black discontent and action within a predominantly white, ostensibly progressive society. Green reveals little-known historical characters among the black men and women who moved to Minnesota following the Fifteenth Amendment and delves into the delicate balance of power between black activists and the state’s progressive white society. Within this absorbing, often surprising, narrative we meet “ordinary” citizens, like former slave and early settler Jim Thompson and black barbers catering to a white clientele, but also personages of national stature, such as Frederick Douglass, Booker T. Washington, and W.E.B. Du Bois, all of whom championed civil rights in Minnesota. And we see how, in a state where racial prejudice and oppression wore a liberal mask, black settlers and entrepreneurs, politicians, and activists maneuvered within a restricted political arena to bring about real and lasting change.

- Why did the author choose the title “Degrees of Freedom?”

- Who were the “race men” of Minnesota and why were they so important? Did their roles change over time? Why or why not?

- Who were the “white patrons” described in the book? Did they have a positive or negative impact on black progress in Minnesota? How did their views and understanding of the black situation in the state compare to that of the race men?

- Why does the author focus on barbers as key figures in the black community in Minnesota? What did they do?

- Why was the creation of the black press in Minnesota so important? What did the editors/publishers do? What did the papers provide?

- How were the cities of Minneapolis and St. Paul different from each other? How did their ethnic and political composition affect black progress in the state? Do they remain different throughout the time period examined?

- Who was Booker T. Washington and why was he a hero to many whites and to some blacks? Why was he controversial? Did he help or hinder the movement in Minnesota?

- Who was W.E.B. DuBois? Why was he a hero to many and an anathema to others? How did he and Booker T Washington disagree about the direction of civil rights movement? Why did he create the Niagara Movement?

- What role did black Minnesotans play in the creation of the Niagara Movement and the creation of the NAACP? Why were both controversial?

- Assess the place and position of Minnesota’s black citizens in 1912, when the book ends. What has changed? What has not?

- Which Minnesota men would you list as most important to the progress of black citizens in the state during the 1865-1912 time period? Why?

A professor of history at Augsburg College and the former superintendent of the Minneapolis Public Schools, William D. Green is also the author of A Peculiar Imbalance: The Fall and Rise of Racial Equality in Minnesota, 1837-1869. He has published many pieces on history and law, including work in Minnesota History and The Journal of Law and Politics, as well as editorials in the Star Tribune.

Degrees of Freedom picks up where your previous book, A Peculiar Imbalance, left off. What initially inspired you to explore this aspect of Minnesota history? Did you expect it to become a multi-book project from the outset?

I felt that it was a history that needed to be told, and in “telling” it, I hoped to offer a way to address contemporary racial matters using history as a means for context. Soon after beginning my work on A Peculiar Imbalance, I realized that the book would only prompt more questions. In a sense, Degrees of Freedom is about a wholly separate interracial experience which bridged the past with more contemporary issues. To do that story justice, I knew I needed to write a new volume. I can foresee a third volume that focuses on Minneapolis during the first two decades of the 20th century.

Could you describe some of the research you undertook in writing these books? What challenges did you encounter in the process?

I had to rely on newspapers, governmental documents, letters, memoirs and various private collections. The history was there; it was a matter of knowing how to adjust my sight to see it. In this area of history there are a lot of gaps that need to be filled in. The biggest challenge I faced was being humble and true to the subject rather than giving into the conceit of hero-worship.

What do you hope readers will take away from Degrees of Freedom?

I hope readers reassess for themselves their sense of “privilege” and “power.”

When and why did you decide to become a historian? What do you enjoy most about teaching history in your current role at Augsburg College?

I have been interested in history since I was a kid. My parents indulged my interest by taking me to sites and museums, introducing me to people I later came to realize were historical figures (W.E.B. Dubois, Martin Luther King, Thurgood Marshall).

Teaching history is best for me when I can see students make connections in their lives with the past, when I can see that they have gained insight, when their insight affirms for me hope in our future.

Tell how you came to reside in Minnesota and how the particular community in which you live has affected your work as a writer.

I came to Minnesota for college and quickly found that few ever said a word about their own past. At first, I thought they were withholding valuable information. I learned, rather, that they had simply dismissed it. It seemed, no “credible” educator valued Minnesota stories and that the “authentic” history had to be boring and irrelevant. I thought I could do better. It was at least worth a try. I learned that to connect with people, I had to employ the age-old approach of telling stories. In this, history becomes a communal effort.

What are you working on now?

I’m working on a couple projects. In one, I examine Minnesota during the period of Reconstruction as it struggles to integrate immigrants, blacks and farmers into a new economy. The other project examines the establishment of a liberal political tradition in early Minnesota.

Watch the short film that was presented at the 28th Annual Minnesota Book Awards.